Kenya's Journey to Constitutional Reform: From Independence to the 2010 Constitution and the Unfulfilled Promise of Executive Accountability

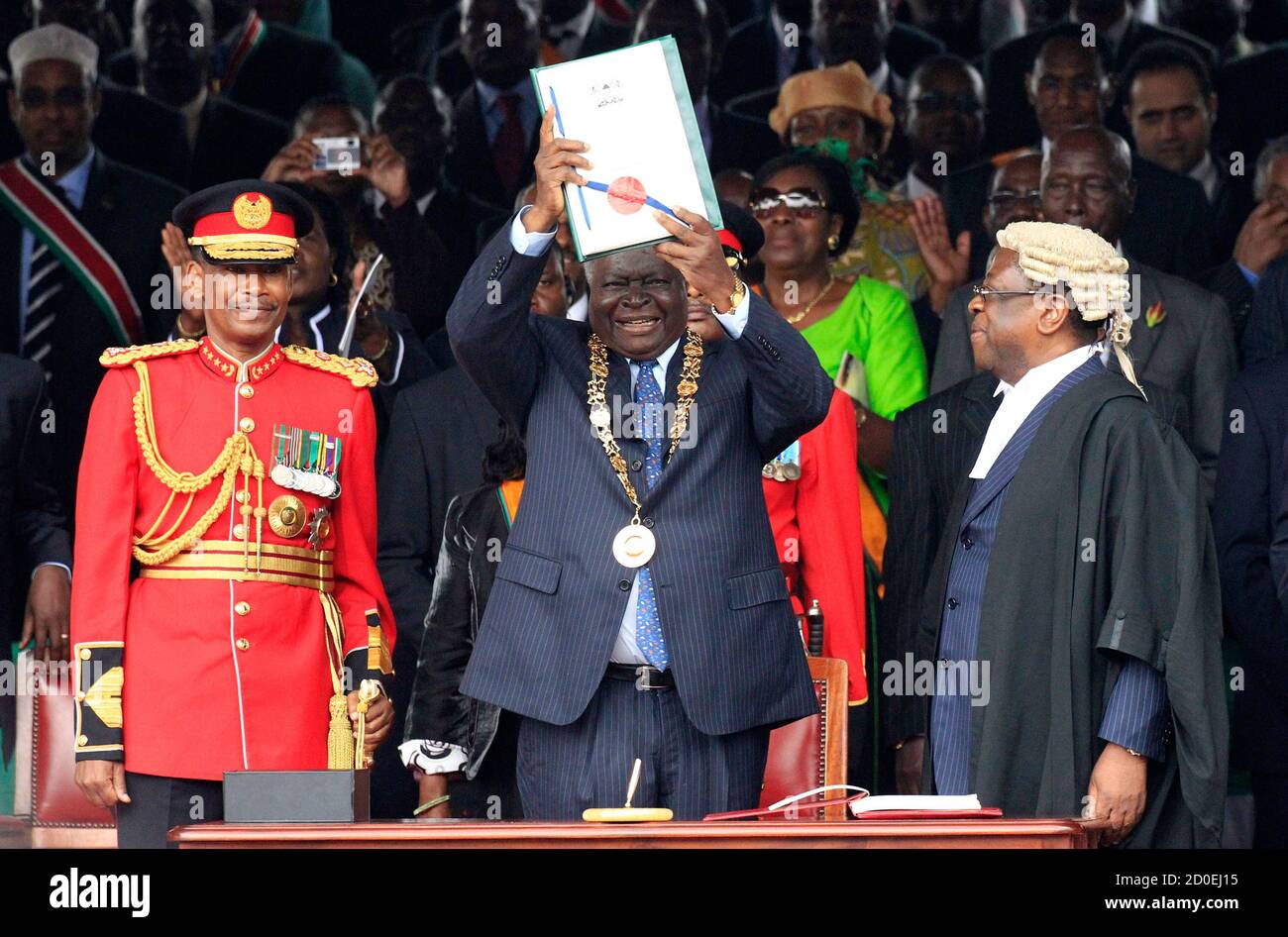

Kenya’s pursuit of constitutional reform has been a protracted struggle, marked by political upheaval, public activism, and hard-fought compromises. The culmination of this journey—the promulgation of the 2010 Constitution—was hailed as a historic triumph for democracy. However, a closer examination reveals stark contrasts between the final document and the earlier Bomas Draft (2004), particularly regarding the structure of the executive branch. While the 2010 Constitution introduced significant reforms, its retention of a centralized presidency underscored a critical divergence from the aspirations of many Kenyans who sought to dismantle imperial presidential powers to prevent abuse.

Historical Context: The Roots of Executive Dominance

At independence in 1963, Kenya adopted a Westminster-style constitution that established a parliamentary system with a ceremonial president and an executive prime minister. However, under Jomo Kenyatta and later Daniel arap Moi, constitutional amendments systematically concentrated power in the presidency, eroding checks and balances. By the 1990s, calls for reform grew louder, driven by civil society groups like the National Convention Executive Council (NCEC), which demanded a participatory process to curb executive excesses.

The 2005 Wako Draft, proposing a hybrid executive, was rejected in a referendum, reflecting public distrust of elite-driven reforms. The 2007–08 post-election violence, however, became a catalyst for change. The National Accord, brokered by Kofi Annan, temporarily introduced a power-sharing government with a prime minister, signaling a shift toward diffusing executive authority. This arrangement was informed by the Bomas Draft, which had emerged as the people’s blueprint for a transformative constitution.

The Bomas Draft vs. the 2010 Constitution: A Tale of Two Visions

The Bomas Draft, crafted through extensive public participation, envisioned a dual executive to prevent the concentration of power.

Key features included:

1. Prime Minister as Head of Government: The President would serve as a ceremonial head of state, while the Prime Minister, appointed from Parliament’s majority party, would oversee governance.

2. Shared Executive Powers: Critical decisions (e.g., cabinet appointments, dissolution of Parliament) required consensus between the President and Prime Minister.

3. Robust Checks on Presidential Authority: Parliament could veto key presidential actions, and the judiciary’s independence was fortified.

In contrast, the 2010 Constitution reverted to a presidential system with a fused head of state and government. Despite introducing term limits and devolution, it preserved vast presidential powers:

- Sole Authority Over Appointments: The President unilaterally appoints cabinet secretaries, judges, and independent commission heads, subject only to parliamentary "rubber-stamp" approval.

- Control Over the Legislature: The President’s role as party leader often ensures loyalty from legislators, undermining parliamentary oversight.

- Emergency Powers: The President can declare emergencies and deploy security forces with minimal accountability.

Why the 2010 Constitution Fell Short on Executive Reform

The dilution of the Bomas proposals stemmed from political negotiations among elites wary of losing influence. The Committee of Experts, tasked with reconciling divergent drafts, faced pressure from MPs and former President Mwai Kibaki’s administration to retain a strong presidency. The abolition of the Prime Minister role—a key feature of the post-2008 power-sharing government—was particularly contentious, revealing a gap between public sentiment and elite interests.

Critics argue that the 2010 Constitution missed an opportunity to address Kenya’s history of authoritarianism. By retaining unilateral presidential powers, it left room for abuses reminiscent of the Moi and Kenyatta eras. For instance, the President’s ability to appoint the Chief Justice and Director of Public Prosecutions risks politicizing institutions meant to hold the executive accountable.

Legacy and Ongoing Debates

While the 2010 Constitution advanced devolution, bill of rights, and judicial independence, its executive framework remains a vulnerability. Recent debates, including the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI), have reignited calls to revisit the structure of the executive, with proposals for a rotating prime minister or expanded parliamentary oversight.

Kenya’s 2010 Constitution was a milestone, but its compromise on executive power reflects unresolved tensions between popular aspirations and political pragmatism. The Bomas Draft’s vision of a balanced, accountable executive remains an unfulfilled ideal. As Kenya continues to grapple with governance challenges, the need to decentralize presidential authority—a demand rooted in decades of struggle—endures as a critical frontier for constitutional reform. Until then, the specter of an imperial presidency looms, a reminder of the work still undone.

The Dual Role of the President: Head of State and Head of Government

Kenya’s 2010 Constitution consolidated executive authority in the presidency, merging the roles of Head of State and Head of Government. This fusion contrasts sharply with the Bomas Draft (2004), which proposed a dual executive system to prevent autocracy. Under the current framework, the President wields unparalleled influence over national governance, raising concerns about accountability and abuse of power.

Concentration of Power: Risks and Historical Parallels

The President’s dual role enables unilateral decision-making in critical areas:

- Appointment Powers: The President appoints cabinet secretaries, judges, and heads of independent commissions (e.g., IEBC, EACC), often with minimal parliamentary scrutiny. For instance, the controversial 2021 reappointment of Auditor-General Nancy Gathungu highlighted fears of executive overreach.

- National Security Control: The President commands the military and approves security deployments, as seen during the 2017 election crisis and the COVID-19 curfew enforcement, which critics argued prioritized political control over civil liberties.

- Legislative Influence: By chairing the National Security Council and leveraging party loyalty, the President shapes legislative agendas, undermining Parliament’s oversight role.

Comparatively, the Bomas Draft sought to diffuse these powers by creating a Prime Minister (Head of Government) accountable to Parliament, while the President (Head of State) would focus on ceremonial and symbolic duties. This model, akin to Germany’s parliamentary system or India’s presidency, reduces conflict of interest and institutionalizes checks on executive actions. Kenya’s retention of a fused presidency echoes pre-2010 authoritarian tendencies, where leaders like Daniel arap Moi exploited centralized power to suppress dissent.

Case Study: Judicial Appointments

The President’s authority to appoint the Chief Justice and Attorney General, ostensibly with parliamentary approval, has led to perceptions of a politicized judiciary. For example, the 2016 appointment of Chief Justice David Maraga faced allegations of executive interference, despite his eventual independence. In contrast, the Bomas Draft proposed a judicial service commission with autonomous appointment powers, insulating the judiciary from executive manipulation.

Governors: Elected Leaders vs. Appointed Technocrats

Kenya’s 2010 Constitution introduced elected governors to lead 47 devolved counties, aiming to enhance local accountability. However, the electoral system has drawn criticism for prioritizing populism over service delivery.

Elected Governors: Accountability vs. Short-Termism

Proponents argue that elected governors ensure democratic representation, as seen in Makueni County, where Governor Kivutha Kibwana’s participatory budgeting improved healthcare and education. Conversely, electoral pressures often incentivize patronage. For example:

- Nairobi Governor Mike Sonko (2017–2020) prioritized high-profile stunts (e.g., distributing wheelbarrows) while neglecting waste management, leading to a national government takeover.

- Hawker Management: Governors like Nairobi’s Johnson Sakaja face dilemmas enforcing city bylaws against street vendors, who constitute a significant voting bloc. This tension underscores the trade-off between political survival and effective governance.

Appointed Governors: Technocratic Efficiency vs. Democratic Deficit

An alternative model—appointing governors as technocratic administrators—could prioritize merit over politics. Rwanda’s system, where mayors are appointed by the central government, has driven rapid urbanization and service delivery. However, this risks alienating citizens, as seen in Uganda, where appointed local leaders are perceived as unaccountable.

Term Limits: Seven-Year Single Term Proposal

A single seven-year term could reduce re-election pressures, allowing governors to focus on long-term projects. Mexico’s non-renewable six-year presidential term has curbed electoral manipulation but also fostered complacency. In Kenya, such a reform might mitigate patronage but could weaken accountability, as leaders face no electoral consequences for poor performance.

Administration Police and County Enforcement

The 2010 Constitution retained the Administration Police (AP) under the National Police Service, rejecting proposals to decentralize them to counties. This has hampered enforcement of county laws, from trade regulations to environmental protection.

Centralized Policing: Challenges for Devolution

Counties lack direct control over law enforcement, creating gaps in implementing County Legislations. For instance:

- Nairobi County struggles to evict encroachers from riparian lands due to reliance on national police, who prioritize national security over local issues.

- Kisumu County’s attempts to regulate street lighting and waste disposal have been undermined by poor coordination with AP units.

County-Controlled Police: Lessons from Global Models

Devolving the AP to counties could mirror U.S. state police systems, where local agencies enforce state laws while federal police handle cross-jurisdictional crimes. However, Kenya’s ethnic tensions and weak county capacity raise risks of politicization. For example, Nigeria’s state police have been accused of extortion and ethnic bias, exacerbating insecurity.

A hybrid approach—training county enforcement units under national standards—might balance local needs with national cohesion. The 2018 Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) proposed such reforms, but political resistance stalled progress.

Revisiting the 2010 Constitution: Lessons and Reforms

The 2010 Constitution’s shortcomings reflect a broader tension between transformative aspirations and political pragmatism. Key reforms could include:

1. Splitting the Presidency: Adopting a ceremonial president and an executive prime minister, as proposed in Bomas.

2. Strengthening County Governance: Introducing mixed-term limits (e.g., a single seven-year term) or hybrid appointment mechanisms for governors.

3. Devolving Law Enforcement: Creating county police units under a national regulatory framework to enforce local laws without fragmenting security.

Conclusion

Kenya’s constitutional journey remains incomplete. While the 2010 Constitution advanced devolution and rights, its preservation of a powerful presidency, electoral pressures on governors, and centralized policing hinder transformative governance. Learning from global models and past missteps, Kenya must prioritize structural reforms to decentralize power, enhance accountability, and realize the democratic promise of its constitutional struggles. The specter of an imperial presidency and ineffective devolution will persist until these systemic issues are courageously addressed.

The writer is an Advocate of the High Court of Kenya and a political analyst

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!